The best information we can ever provide investors is the mechanics of how we think about macro conditions over time, rather than what we think about them at any particular time. Consistent with this idea, we present our Macro Mechanics, a series of notes that describe our mechanical understanding of how the economy and markets work. These mechanics form the principles that guide the construction of our systematic investment strategies. We hope sharing these provides a deeper understanding of our approach and ongoing macro conditions.

US Treasuries have been some of the most challenging markets to navigate for investors over the last few years. The weakness in bonds began in 2022, with the Fed’s initiation of one of the fastest and largest tightening cycles in decades. The hiking cycle in itself caused significant damage to the treasury market, leading to drawdowns we haven’t seen since the 1970s in fixed income markets. However, to the surprise of market participants, bond markets did not recover and continued to face significant chop for several years, crowned by treasuries actually falling as the Fed began its easing cycle in late 2024.

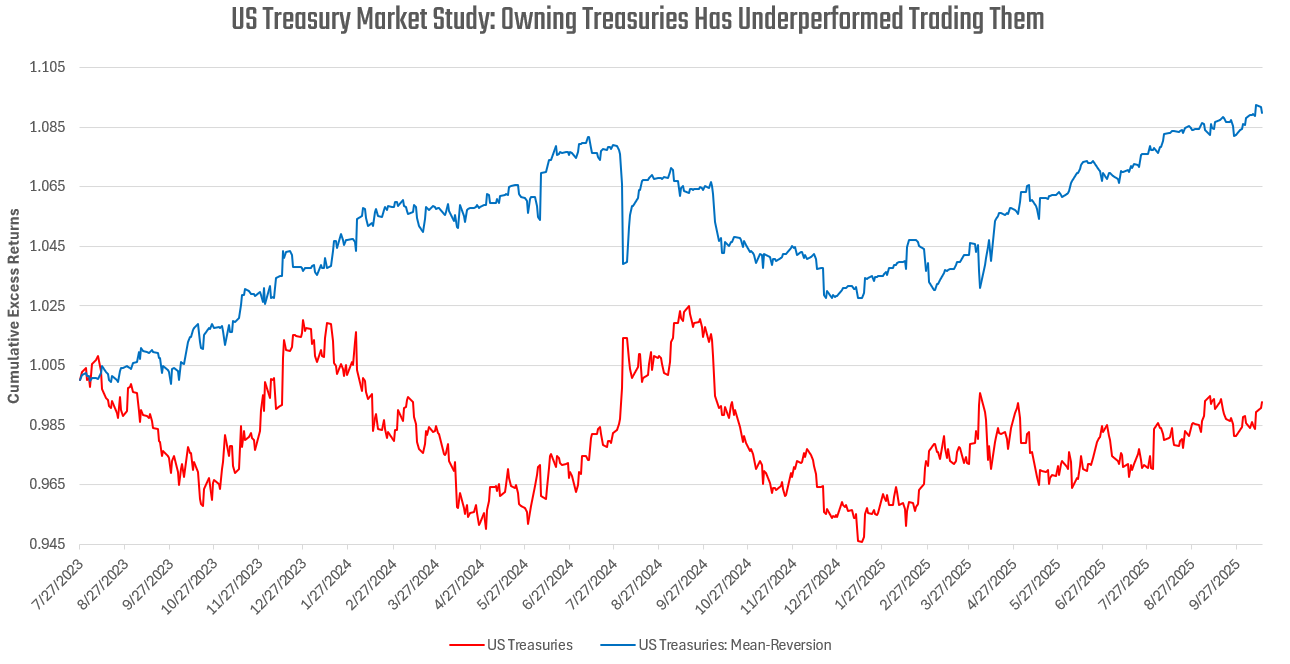

These conditions created a somewhat novel dynamic relative to the long-term history of bonds: one where the price action in bonds was dominated by mean reversion. Those expressing views in line with these mechanics were significantly rewarded, with mean reversion strategies far outperforming simply holding bonds. We visualize this outperformance below, from the prior peak in the Fed Funds rate in 2023:

In this note, we discuss the reasons we think this anomaly has existed, and most importantly: we evaluate whether it can continue.

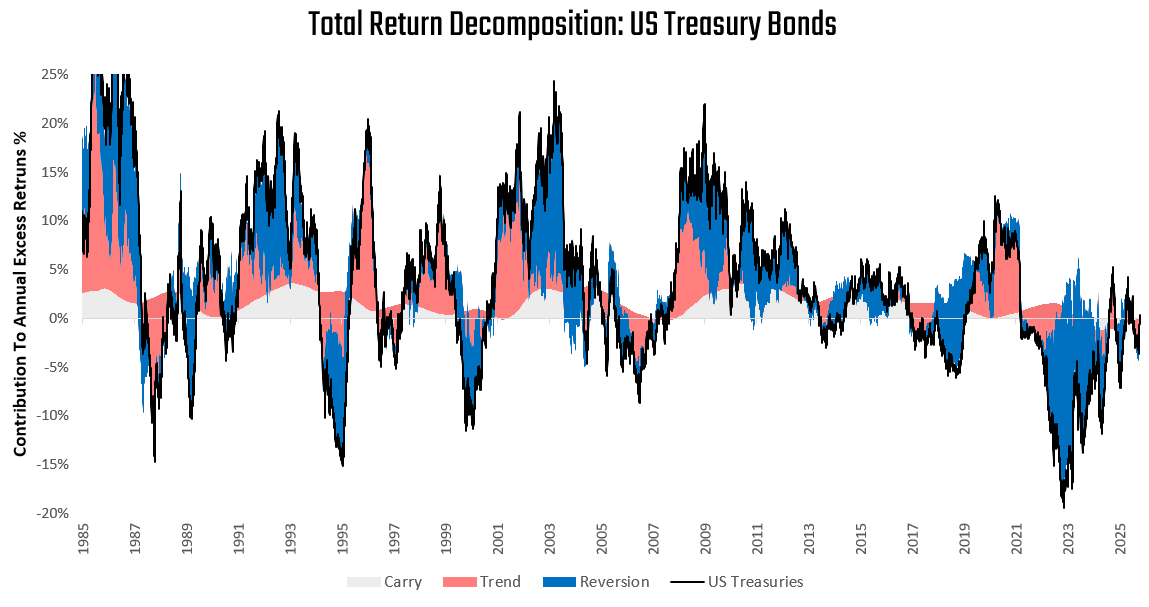

Let us begin with our decomposition of bond returns sources over time:

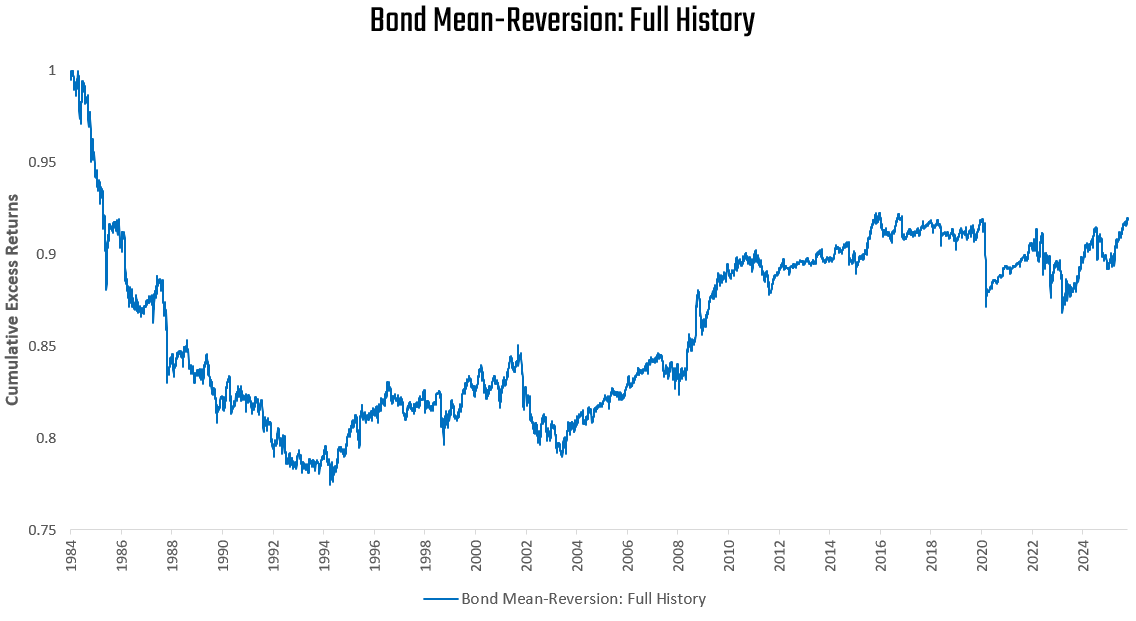

As we can see above, there has been a significant upward shift in the share of our decomposition of bond returns explained by mean reversion since the 2022 hiking cycle. This is what enabled the previously illustrated bond-mean reversion strategy to perform so well. However, without this shift, the performance of this strategy was far weaker:

As we can see above, bond mean-reversion is not a standalone strategy that can continue to deliver excess returns. Unless the macro environment remains conducive.

To understand the macro factors driving these conditions, we begin with our macroeconomic decomposition of the returns of a treasury security. The changes in its yield drive the returns on a treasury bond. This yield is driven by changes in the short rate, expectations for the changes in the short rate, and the term premium. The expectations for the short rate are driven primarily by the evolution of the drivers of monetary policy. The term premium is driven by liquidity constraints of those further out on the curve and their ability to absorb treasury supply. Between the short rate expectation and the term premium, short rate expectations are by far the dominant driver of variation in the total returns of a bond.

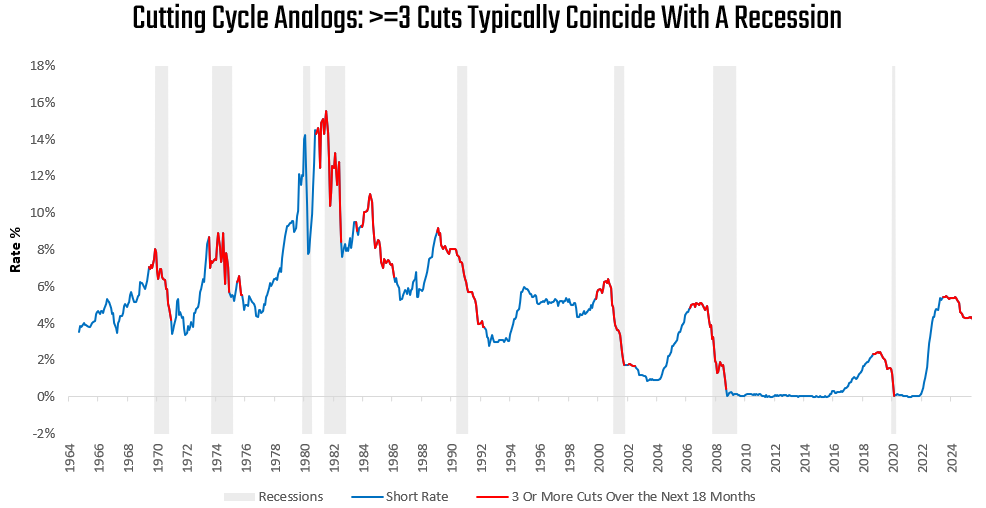

This is where we have also seen the most action in terms of bond mean-reversion, i.e., expectations for monetary policy have continued to whipsaw dramatically over the last few years, to an extent seen before in history. The driving force behind this has been the stark contrast between the expected path of monetary policy, which has consistently anticipated easing, and the backdrop of elevated nominal activity, which has consistently suggested tighter or stable monetary policy. Markets have essentially expected three or more cuts ever since the hiking cycle began in 2022, regardless of the level of nominal GDP. This pricing, by historical measure, is almost always consistent with a recession:

The notable exception is, of course, the period from 1984 to 1986. However, this was a period of dramatic growth deceleration.

Nonetheless, the pricing of treasuries over the last few years has largely been consistent with a significantly slowing economy. While the economy has indeed slowed, it has largely not met the expectations embedded in the bond market.

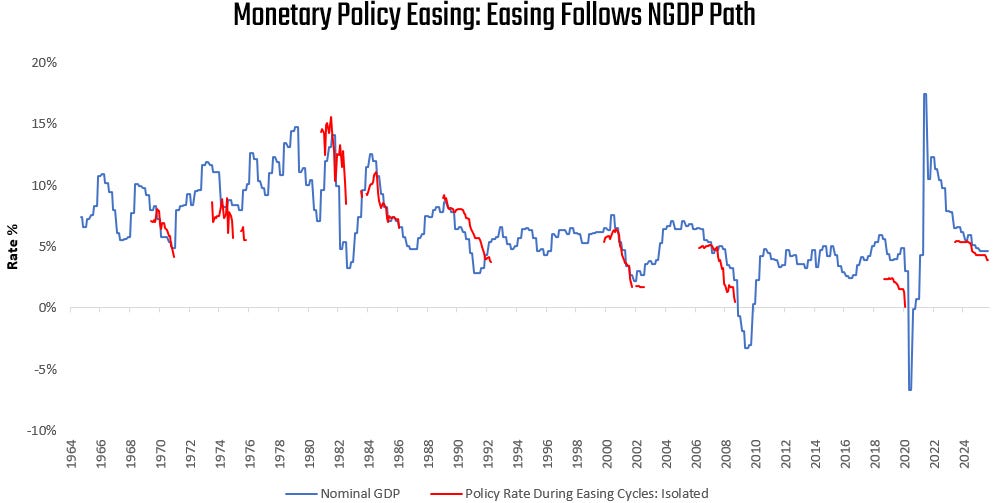

Below, we show how meaningful monetary policy easing, including “insurance easing”, typically follows the NGDP path in terms of its delta:

As ever, the purpose of our Macro Mechanics is not to give you a market view, but rather to share our mechanical approach to markets.

Thus, when we examine the question: Will Bond Markets Continue to Mean-Revert? Our answer is: it depends on whether they are pricing the most likely path of nominal GDP. The greater the divergence between the growth expectations embedded in monetary policy and the future pace of nominal GDP, the greater the mean reversion potential.

Until next time.