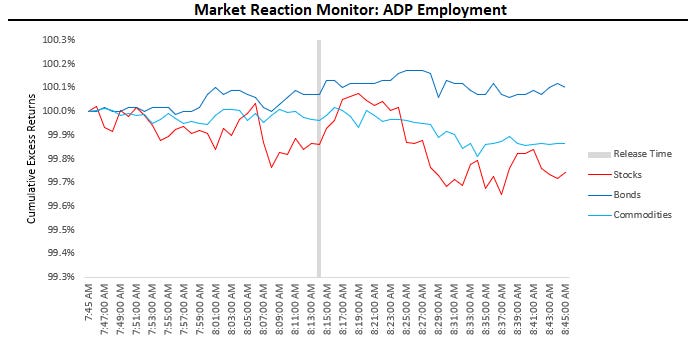

The latest ADP data moved markets modestly, coming in hotter than expected. Jobless claims came in hotter than expected. Overall, equities were lower, bonds were higher, and commodities were flat.

We’ll receive data on nonfarm payrolls and household survey jobs later this week. Ahead of these highly anticipated releases, we want to take a step back and contextualize our thoughts on the labor market cycle. Let’s dive in.

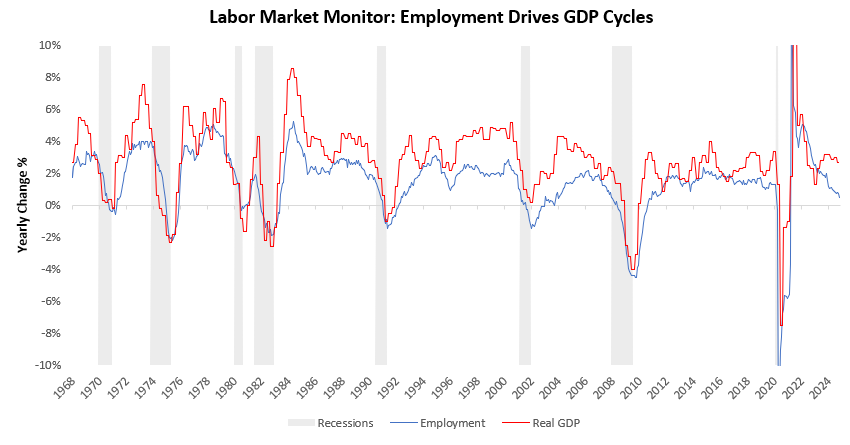

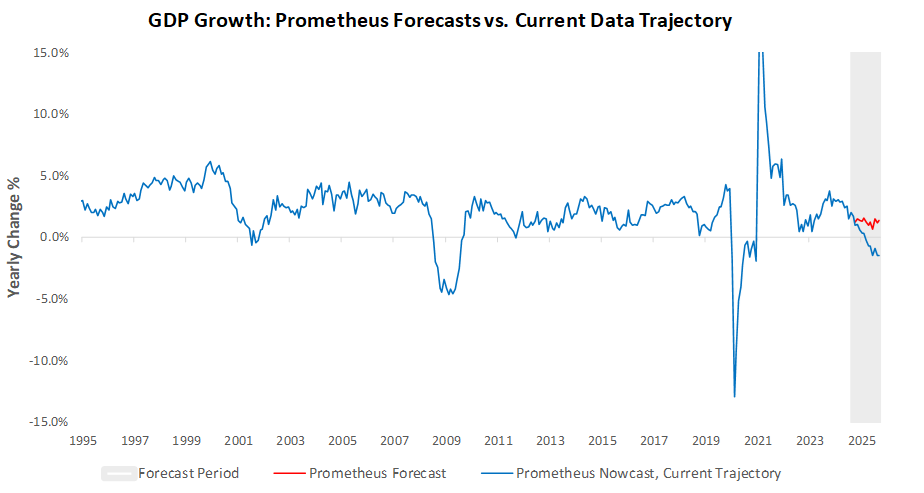

The labor market is dominant in driving variation in overall economic activity. While business cycle pressures may originate in other areas of the economy, the labor market is the ultimate transmission mechanism for cyclical conditions to aggregate spending and income. Below, we visualize how employment growth explains most of the variance of GDP in a time-varying manner. Notably, during expansions, employment sets the baseline trend for GDP growth, while during recessions, job losses explain almost all of the contraction in activity:

GDP is rich versus employment growth, and while this dynamic can continue for a little while, we don’t expect it to continue much longer. A big driver of this gap has been inventory growth, and that growth is fading based on our timely readings.

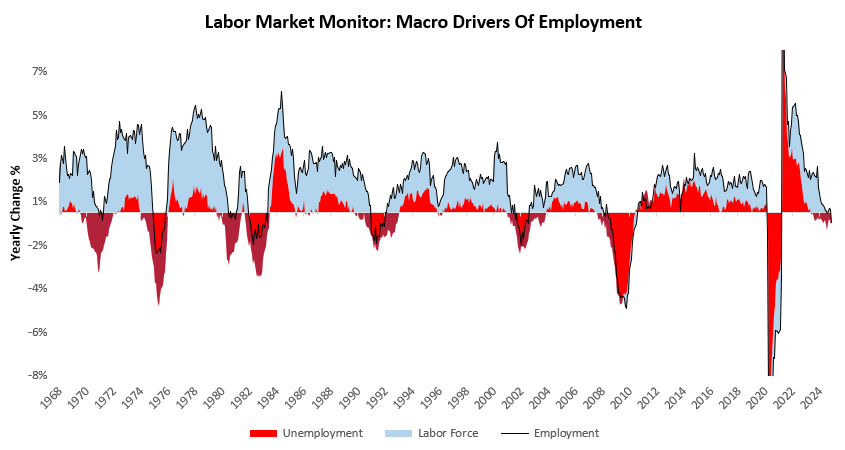

To further understand what drives labor market growth, we decompose employment growth into its primary macro drivers, i.e., labor force and unemployment changes. A growing labor force supports the steady expansion of the labor market. Meanwhile, changes in unemployment largely stem from cyclical conditions. During expansions, unemployment falls, driving up employment, and during contractions, unemployment drives downturns in employment:

Unemployment has begun to rise in a manner consistent with the slowing of the economy we see in our timely reads of economic activity.

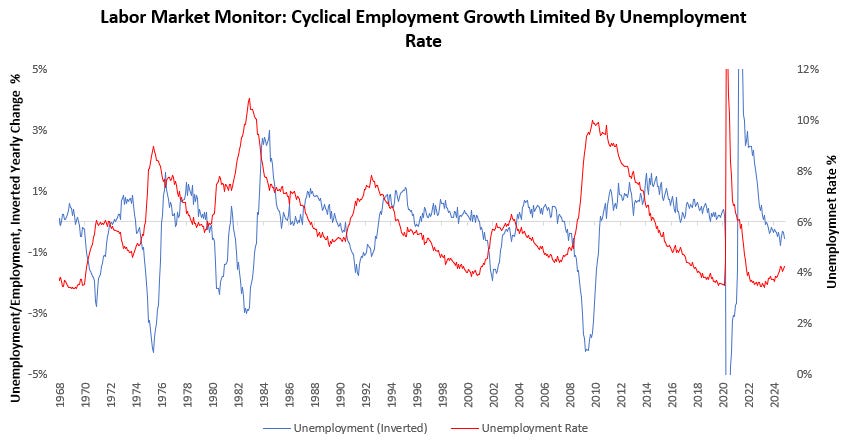

While labor force growth driven by population trends drives the long-term trajectory for employment growth, the job market's cyclical variation primarily comes from changing unemployment. However, cyclical changes in unemployment are limited by unemployment rates. Once again, this dynamic is somewhat skewed. Declining unemployment is capped by unemployment falling below the natural unemployment rate or zero at the limit. Increases in unemployment have less of a hard ceiling, but practically, an extremely high unemployment rate is likely to create conditions that constrain population and labor growth. Thus, the unemployment rate largely constrains the cyclical movements of labor markets. We visualize this below:

Unemployment rates are rising, and unemployment rates are low, suggesting significant room for further increases if current trends persist.

Now that we have examined the big-picture macro drivers of labor markets, we can turn to more detailed measures of current labor dynamics. To understand employment's leading and lagging components, we look across employment, unemployment, job openings, and jobless claims. We begin by understanding the current composition of employment growth, broken down by sector:

Manufacturing and retail job losses are driving the current decline in nonfarm payroll growth.

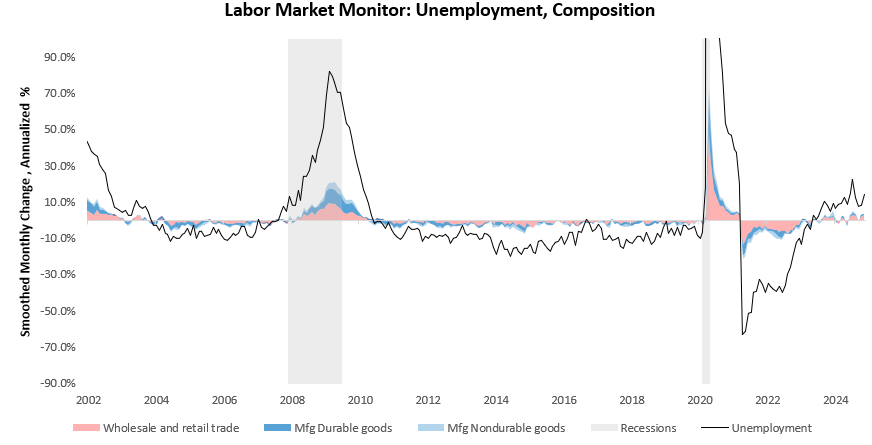

Now that we have examined the drivers of employment growth, we turn to cyclical drivers of these employment changes, i.e., unemployment. Below, we visualize the composition of unemployment changes, broken down by sector:

The latest unemployment data does not confirm this weakness in manufacturing and retail jobs as the primary driver of weakness, but it shows a modest negative pressure coming from these sectors.

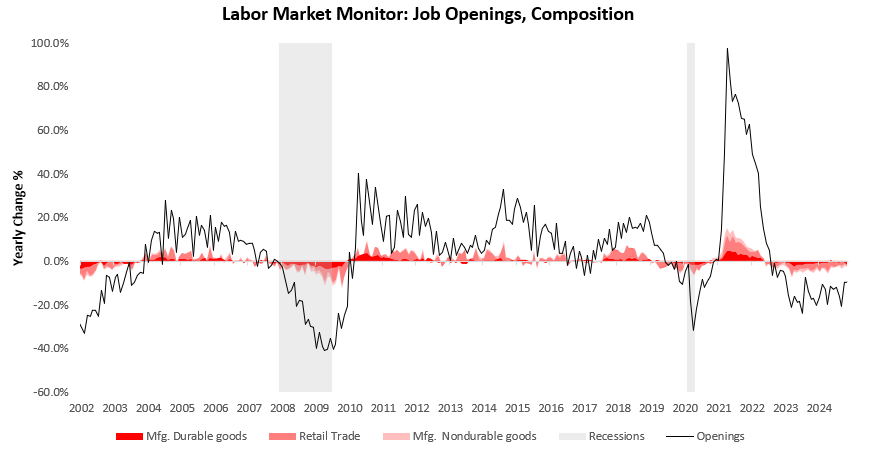

To further understand these cyclical conditions, we now turn to job openings, which drive job growth by expanding the opportunity set for employment. Expanding job openings indicate strong business conditions and potentiate employment growth. On the other hand, contractionary job openings are likely to result in further unemployment:

We see these manufacturing and retail jobs also dragging on job openings, with aggregate job openings remaining weak.

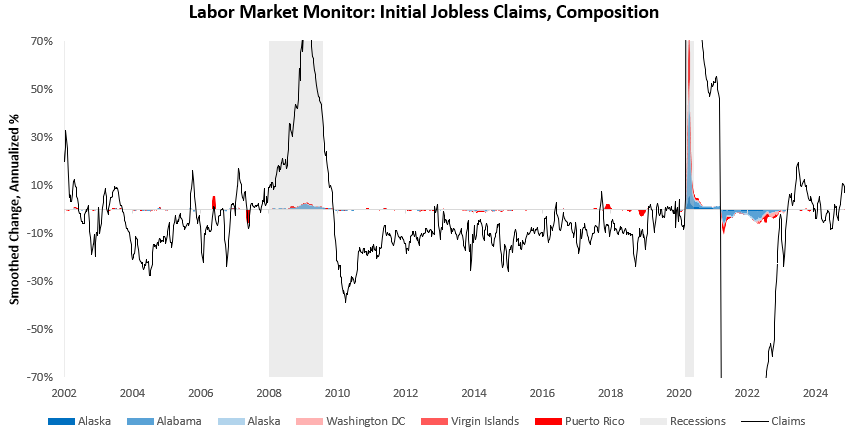

Next, we turn to the timeliest measure of emerging pressures on cyclical employment conditions, i.e., initial jobless claims. In a weakening labor market, initial jobless claims continue until they are recorded as unemployment numbers. However, in a strong labor market, initial claims are continuously cleared via existing job openings, keeping unemployment stable. As such, compounding jobless claims rates, upwards or downwards, give us a timely insight into cyclical economic changes. Below, we visualize the drivers of these changes, decomposed by the state:

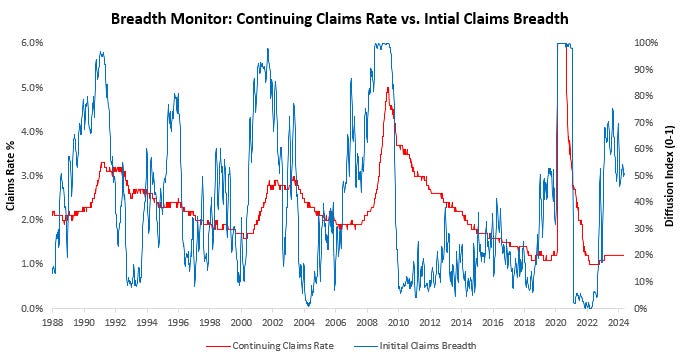

Jobless claims have risen in the recent past. Jobless claims are secularly low, cyclically stable, and sequentially rising. We show each perspective.

Starting with the secular.

Jobless claims are secularly low.

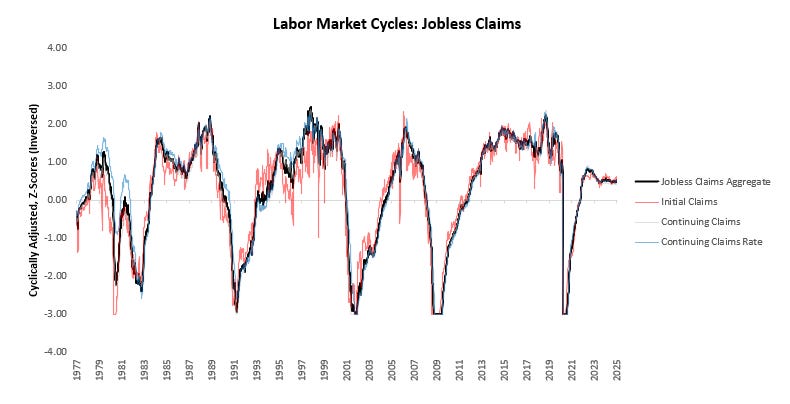

Turning to cyclical.

Jobless claims are cyclically stable.

We end on the sequential. We show jobless claims data sequentially to understand where we are in the labor market cycle relative to the most recent cycle peak. As of our latest reading, our labor market measure shows that jobless claims are at 23%. Recessions typically begin around a reading of 18%, suggesting we are within the ballpark of recessionary territory.

Jobless claims are sequentially rising.

This sequential decline remains fairly broad-based:

Approximately 50% of states are still seeing rising jobless claims rates.

The biggest concern for today’s jobs markets is the weakness in the manufacturing sector. We visualize the diffusion of employment growth for durable goods manufacturing below:

Durable goods manufacturing is seeing pervasively weak job growth. This has a weight on overall job growth, but it is not enough to bring the economy into a recession; it is more likely to result in a slowing of labor growth.

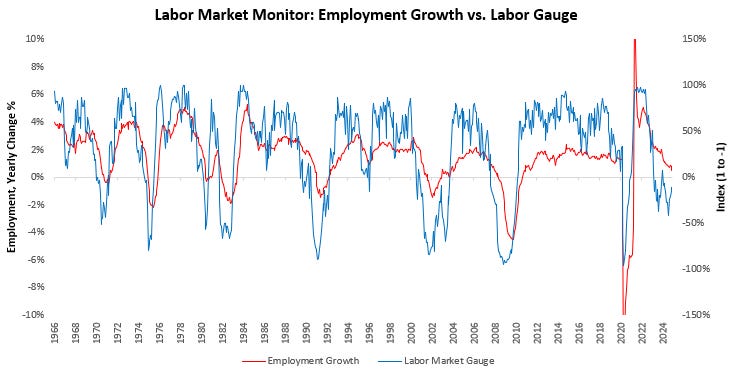

Consistent with these labor market dynamics, our proprietary Labor Gauge suggests weakness in labor markets.

We see this reflected in recent labor market trends, which, if extended, would result in neutral employment growth in 2024. We visualize our data trajectory monitor, which extracts the current trend of the data and projects it into the future to understand the likely better path of annualized data.

On the current trajectory, labor markets are headed toward neutral growth in 2025. We expect jobs data to be better than recent trends, but we think recent trends are consistent with the broader economic pressures. Labor markets are far from recessionary but show increasing signs of slowing. We reiterate our forecast for GDP growth below:

Until next time.