We started Prometheus with a simple mission: to bring the best institutional investing tools to everyday investors. In line with this mission, we’re taking the next step—making our economic research free of cost. In this note, we describe why we are taking this step and why we believe it is in the best interest of all investors.

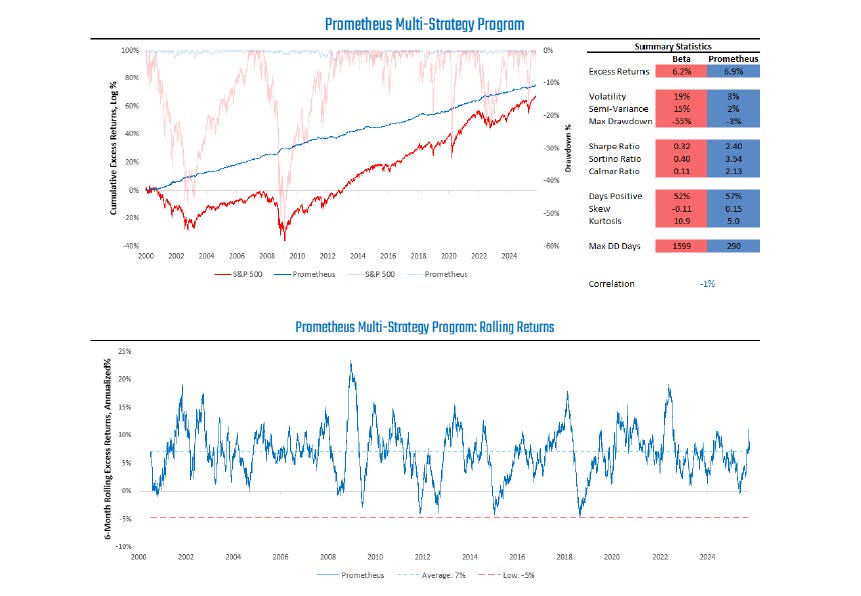

Prometheus is built on years of consistent and diligent tracking of every piece of macroeconomic data and translating that data into actionable investment strategies. This process involves creating a systematic framework for tracking the economy and markets, understanding the nuances of hundreds of data releases, mapping the effects of these data on individual markets, and quantitatively forecasting markets on a daily basis. The accumulation of all the things we have learned, from small nuances around the way CPI data is calculated, to cross-asset phenomena like trend following, is embodied in the Prometheus Multi-Strategy Program:

Having spent years turning macroeconomic views into market views, we came to a conclusion a long time ago:

Long-term economic views are useless as standalone investment tools.

Long-term forecasting is an inherently fragile exercise, riddled with statistical uncertainty. Even if one could forecast the economy perfectly over the long run—a heroic assumption—the improvement to an investor’s portfolio would be marginal at best, and often negative. This is deeply counterintuitive for many investors. Further, it runs directly against the foundation of an entire industry built around selling long-term macro opinions to investors, branding narrative conviction as portfolio edge. As always, our views are grounded in quantitatively verified observations. We share some of these observations below.

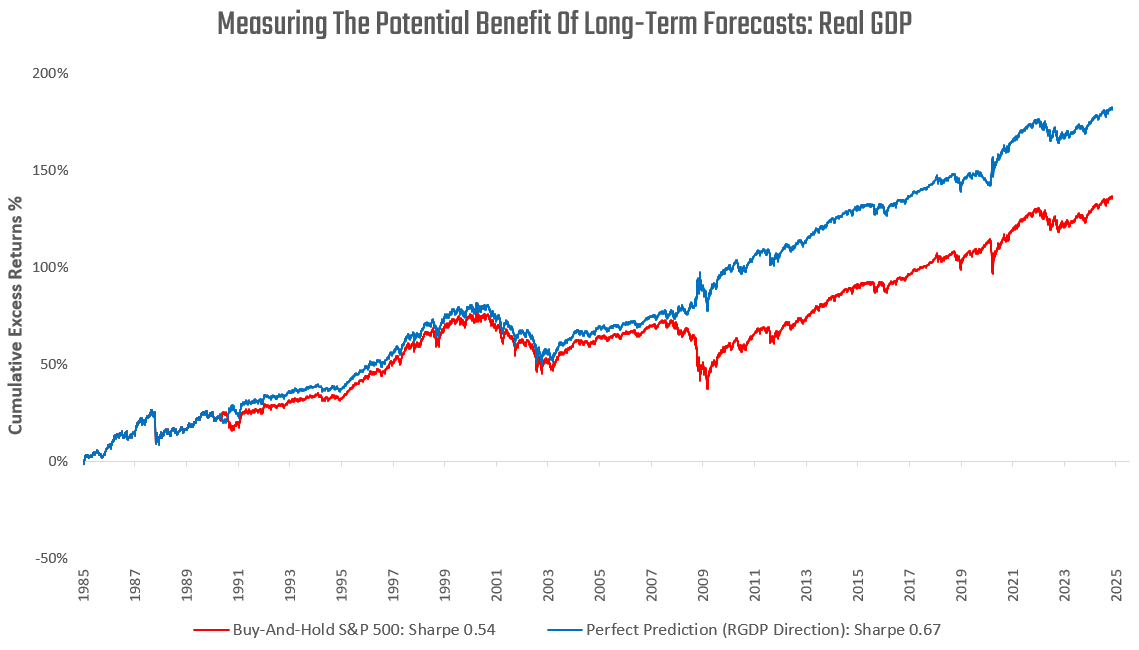

We focus on the equity market for these observations due to its centrality to global investors. We begin by asking the question, “What if we could perfectly predict real GDP growth?” Surely, we would be able to time the market exceptionally well. Reality deviates meaningfully from this expectation, which we visualize below:

Above, we compare the excess returns (over cash) of a buy-and-hold S&P 500 position with a dynamic strategy based on a perfect directional prediction of real GDP one year forward (Perfect Prediction). If real GDP over the next year is positive, the strategy goes long the S&P 500; if real GDP is negative, it goes short the S&P 500. Rebalanced daily. As we can see, perfectly predicting the direction of real GDP since 1985 does indeed yield some additional benefits, but it just barely moves the risk-adjusted return of the portfolio. Modestly decreasing the hit rate of the GDP forecast would effectively nullify any improvements to total returns. Therefore, unless you’re sure that a one-year forecast will have a 100% hit rate, you’re better off just owning passive exposure.

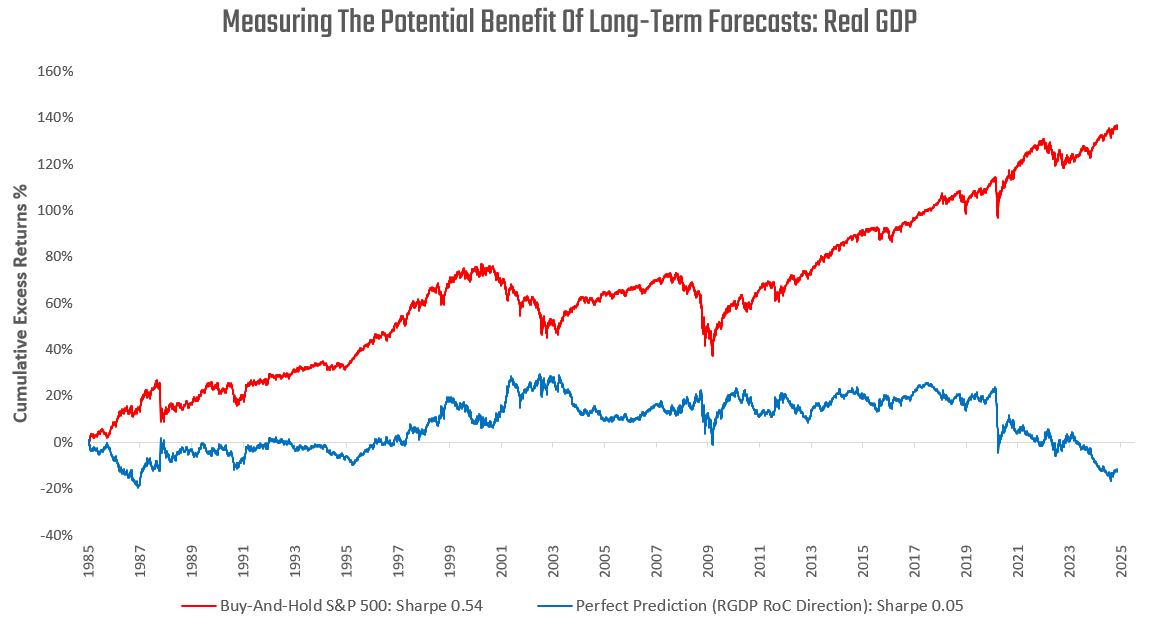

Some may argue that it's not about the binary level of growth, but rather about the direction of the rate of change. We find this approach to be empirically worse, largely because it reduces beta exposure dramatically:

Here, we compare the excess returns (over cash) of a buy-and-hold S&P 500 position with a dynamic strategy based on a perfect directional prediction of the rate of change of real GDP one year forward (Perfect Prediction). If real GDP growth one year forward accelerates relative to its 12-month trailing average, the strategy goes long the S&P 500; if real GDP decelerates, it goes short the S&P 500. Rebalanced daily. As we can see, perfectly predicting the direction of the rate of change in real GDP since 1985 would destroy wealth over time.

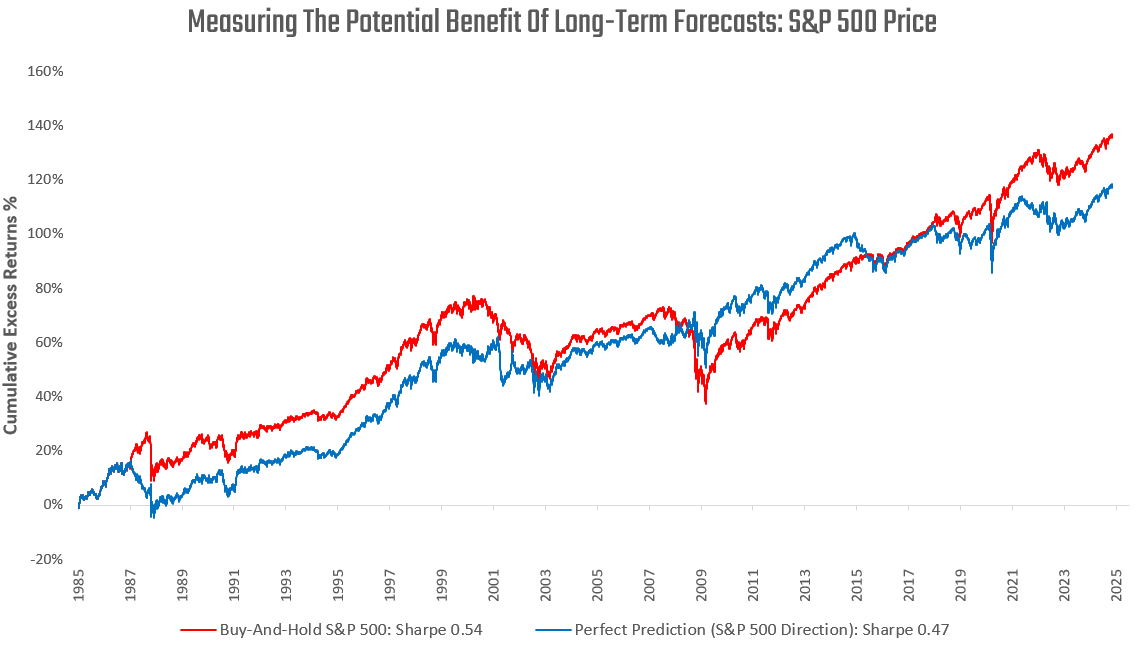

We take this evaluation even further, and ask, “What if we knew whether the price of the S&P 500 would be up or down over the next year?”. Of course, this approach must generate exceptional returns(?). We find intuition denied once again here:

Above, we compare the excess returns (over cash) of a buy-and-hold S&P 500 position with a dynamic strategy based on a perfect directional prediction of S&P 500 total returns over the next one year (Perfect Prediction). If total returns for the S&P 500 are positive over the next year, the strategy goes long the S&P 500; if the returns are negative, it goes short the S&P 500. Rebalanced daily. We see this approach underperforms a simple buy-and-hold strategy. The reason for this underperformance is subtle. While we may know whether the S&P 500 will be down over the next year, we don’t know how that price action will be distributed over the next day, week, or month. Navigating the path of returns is essential for market timing, and long-term forecasts do not provide insight into this path.

While we have focused on equity markets for these observations due to their centrality to global finance, our results are relatively uniform across markets. Long-term forecasts of growth, inflation, and asset prices consistently yield relatively mediocre outcomes compared to passive exposure—even with 100% accuracy on the direction of travel.

Yet, we find that there is an entire industry built around the notions that i) the long-term is more predictable than the short-term, and ii) that adjusting allocations based on these long-term predictions has significant value to investor portfolios. Furthermore, research services built around these ideas often share their long-term views, leaving clients to solve for positioning on their own—which is empirically the most challenging part, as demonstrated above. Often, macro research providers focus entirely on the big picture, with little regard for the intricacies of positioning.

We think these conditions create a misalignment of interest between long-term macro forecasters and their clients. The long-term forecaster remains focused on generating the best possible long-term forecast, despite the fact that this has minimal impact on investor portfolios. Often, this exercise is biased by the need to deviate from consensus, which has an asymmetric business payoff. Predict a boom or bust that nobody else predicts, and your business will benefit massively. The times it doesn’t come along, it matters little because you don’t recommend positions anyway. Meanwhile, the client must contend with the reality that long-term forecasts aren’t reliable ways to manage a portfolio, and even if they were, their accuracy is severely lacking. All of these dynamics come together to make much of the independent macro research business a content-driven business rather than an investment-driven one.

Does this mean that we think all macro research or long-term forecasting is useless and the industry should shut down? Absolutely not. However, we believe that real skill lies in translating macroeconomic views into tradable portfolios with an edge over simply holding beta. Any macro research provider that strives to do that, or enables an investor to do that, is worth every penny they charge. In the near future, we will provide a list of providers that fall into this category. This is also what we endeavour to do with our paid products. Note, this doesn’t mean that every research shop should begin role-playing as a hedge fund manager— but they do need to make sure they are offering value.

At Prometheus, our entire tracking and nowcasting of the economy is built around creating systematic tradeable views. That’s what our process is built for. Given that’s what it’s built for, we understand that basic tracking of the economy and some forecasting is not something you should pay for. Translating macro into forward-looking asset allocations is a complex endeavour requiring skill, which you should pay for, especially if you find someone who does it well.

So if your macro research provider performs exclusively big-picture analysis and leaves you high and dry on what to do in markets— you can get all that for free at Prometheus.

It would be interesting what the results of these tests would be instead of going short the market just holding the funds in a money market find or T-bills instead. If you were more adventurous you could hold them in a mix of T-bills/TLT/TIPS/Gold/Managed Futures to have a low beta place to stash your money.

Shorting is expensive and having the small but still notable SPY div yield adds to the carry cost and increases the likelihood that you lose money if your timing is slightly off, no matter how right your reasoning.