Over the last year, the labor market has sparked significant debate within the macroeconomic community. Real GDP data has continued to power ahead, while the labor market, by various measures, continues to flirt with contraction. These dynamics are highly anomalous relative to history and have created extremely divergent views among macro investors on the current state and outlook for the US economy.

Over the years at Prometheus, we have spent a great deal of time developing timely tracking of economic conditions consistent with GDP accounting. Said differently, for every major economic data series released in the US, we have a quantitative estimate of how it flows into GDP and corporate profits, and how it is reflected in markets.

As such, we think working through these mechanics may offer some clarity to investors at a time when the aggregate picture looks unusually muddled. The objective of this note is to present our mechanical approach for examining the labor market’s effects on three areas:

GDP Growth

Earnings

Markets (Stocks & Bonds)

We then apply that mechanical approach to the current context to offer a conceptual roadmap for navigating today's markets.

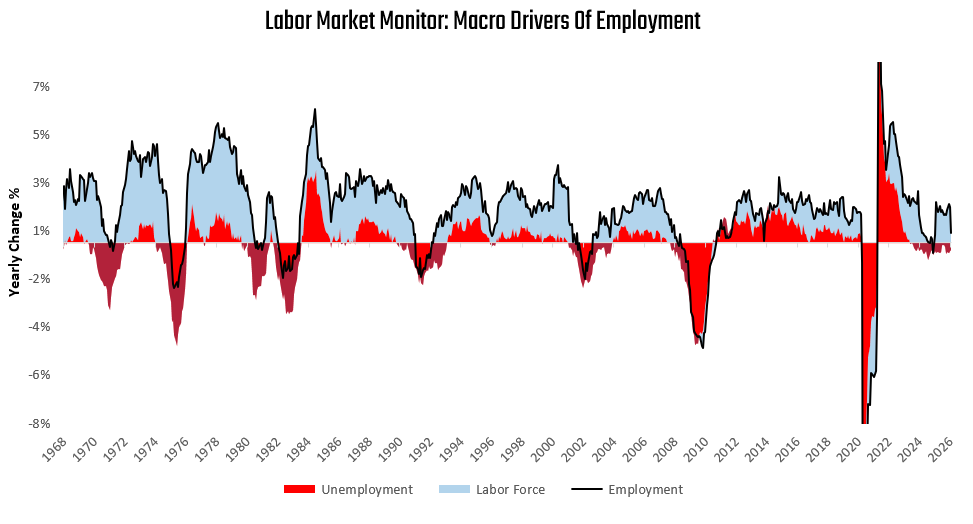

Before diving into the effects of the labor market, we think it is crucial to understand the labor market itself and its drivers. At Prometheus, we think the most important metric for assessing the state of the labor market is aggregate employment growth. Employment growth is the broadest measure of the labor market and reflects both secular and cyclical dynamics in the economy. We can decompose employment growth into three parts:

Population Growth: Population growth is the driver of the long-term trend in employment. Population growth alone does not determine the pace of employment growth; it only potentiates it. How much of that population growth is harnessed through employment depends on participation and unemployment rates. Nonetheless, the secular trend in employment is determined by the pace of population growth. This trend is a slow-moving phenomenon measured over decades rather than years.

Participation Rates: In any given population, only a certain percentage is willing and able to work or participate in the labor force. The higher this participation rate, the higher employment is likely to be at any time. The participation rate is determined by demographic factors, particularly age and nationality. While participation rates are slightly more variable than population growth rates, they too are largely secular phenomena with long, consistent trends.

Unemployment Rates: Unemployment rates account for virtually all cyclical variation in the labor market. For a given population and participation rate, there are only so many employees corporations are willing to hire. During extremely strong business conditions, businesses increase their hiring faster than the labor force grows, so unemployment rates fall. During recessions, businesses reduce their headcounts, leading to higher unemployment rates.

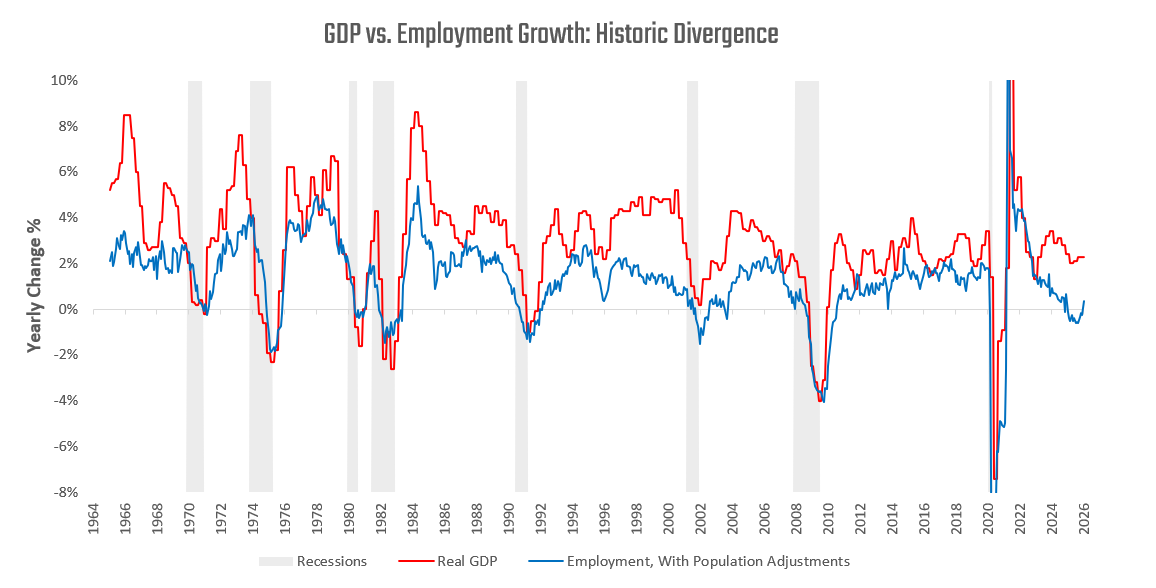

The cumulative effects of changes in population, participation rates, and unemployment rates determine employment growth. Employment growth is the most important driver of economic growth over time, mechanically driving and statistically explaining most changes in output. Employment growth directly leads to income growth, which in turn leads to spending growth. Household income and consumption are the biggest drivers of US economic activity, with employment growth as the primary engine of gains in both. Population and productivity trends slowly feed into trend rates of GDP growth, while shifts in the unemployment rate define cyclical variation. Therefore, employment growth is almost linearly related to GDP growth. The only way output and employment can meaningfully deviate from one another is if output per worker dramatically increases. This rare divergence between output and employment is what we are seeing in today’s economy. We will address this topic further in a later section. Still, for now, we stay with the mechanics—with our primary takeaway that the relationship between employment and output is fairly linear.

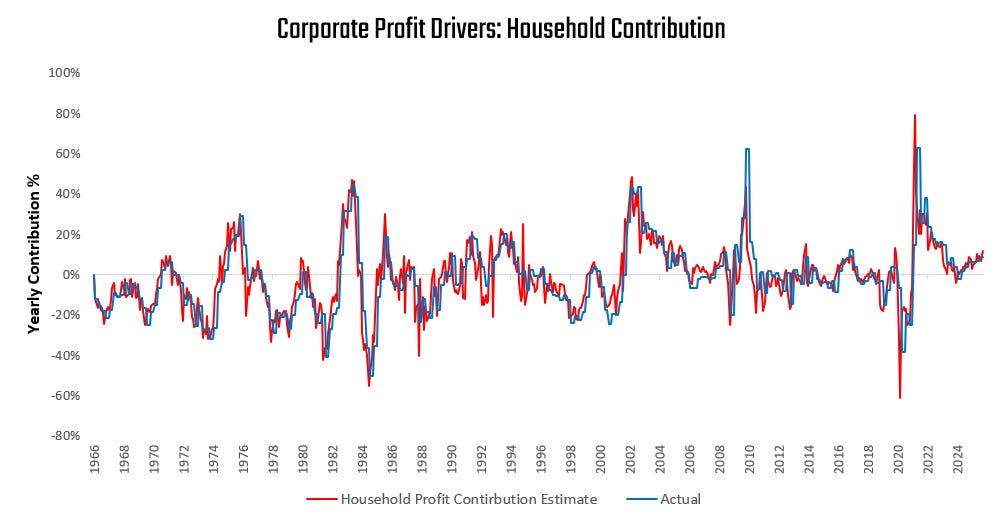

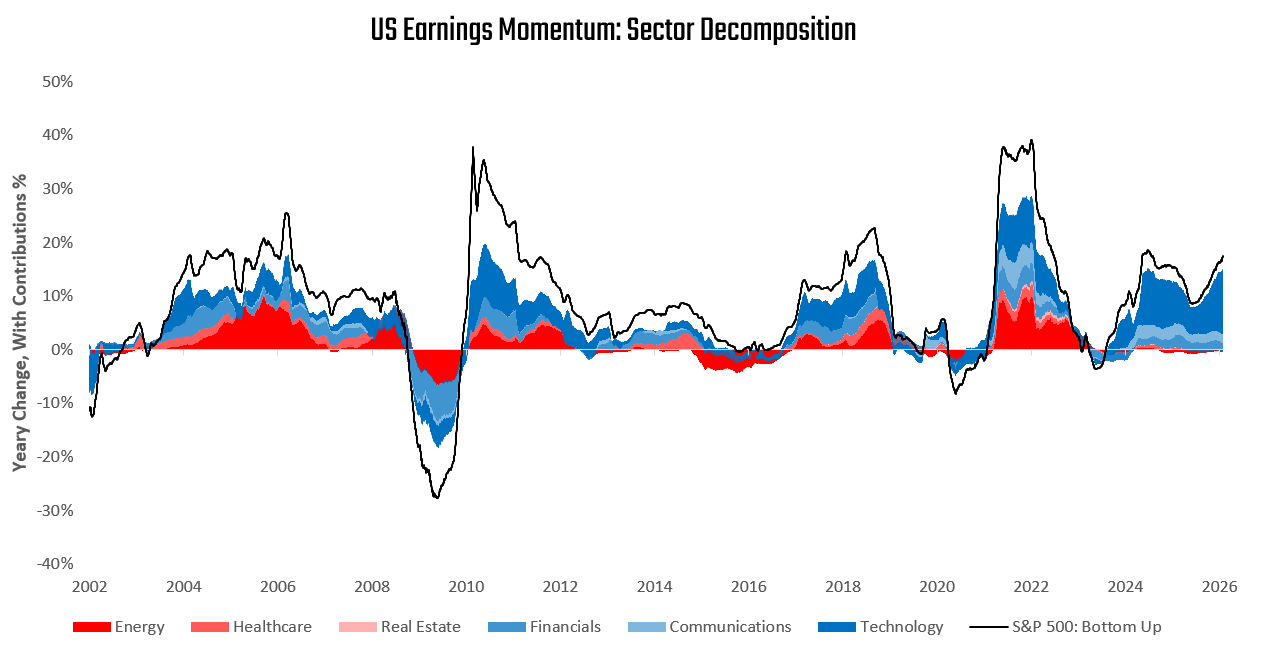

While the linkages from employment to output are direct, the relationship between employment and earnings is more mixed. Employment directly contributes to household income, and rising employment is typically a good sign for corporate earnings. However, it is essential to recognize that every unit of wages paid to households is a cost to businesses. Whether employment is positive for earnings depends on whether households’ rate of spending outpaces their rate of income. This can happen through a reduction in households’ savings rate, the spending down of accumulated wealth, or borrowing against future income. Regardless of the source, for employment to be a net positive for earnings, the growth in wages paid by businesses must be slower than the growth of household consumption. On the same coin, labor market weakness, if offset by higher consumption spending, can often be positive for earnings. We find this to be the case today—employment has been slowing, but spending continues at a strong pace, supporting earnings. While this may be an unintuitive circumstance at the headline level, it remains consistent with our template.

So far, we have discussed the direct impacts of employment on output and earnings. These impacts can largely be traced through the macroeconomic accounts. However, when we turn to the impacts of labor on markets, the effects are less grounded in accounting linkages and more tethered to market pricing. This market pricing is largely dependent on macro market participants’ interpretation of the data and the flow-weighted average interpretation of the expected path of the data. This pricing mechanism is significantly less tight than accounting linkages, but nonetheless consistent over time. We focus on the two major markets: fixed income and equities.

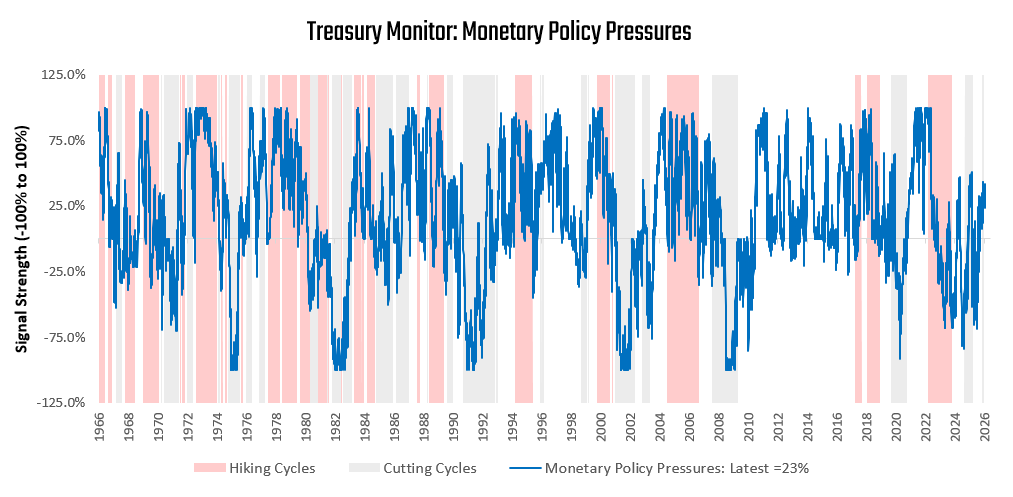

Fixed-income markets are more focused on the effect of labor markets on real GDP, whereas equities are more focused on the effect of labor markets on earnings. We discuss each. Expectations for Federal Reserve policy dominate fixed-income markets (Treasuries in particular). On most days, virtually all of the returns in Treasury markets can be attributed to shifts in policy expectations. Fed policy itself is driven by the Fed’s policy objectives: maximum employment and price stability. The Fed’s full-employment objective makes labor dynamics directly tied to market pricing of expectations about Fed policy. Recall, there are three components of employment: population, participation, and unemployment. The Fed is most concerned with smoothing cyclical variation in the economy and, as such, tends to focus on the unemployment rate and its dynamics rather than on population or participation dynamics. This is because the Fed has a greater ability to influence business cycle conditions through its interest rate policy than to affect long-term demographics. As such, shifts in the unemployment rate or cyclical labor market indicators affect fixed-income markets. These cyclical shifts align with shifts in real GDP, given the fairly linear relationship between labor and output outlined in our earlier sections. As such, the primary avenue for labor concerns to be reflected in markets is via the Treasury market. This pricing also impacts all other asset classes, as expectations for monetary policy impact the discount rate used to discount cash flows across assets. Nonetheless, its effect on Treasuries is the most profound and the principal driver of the asset class.

As noted, discount rate expectations impact all asset classes—which means that cyclical labor market dynamics impact all asset classes. However, they do not necessarily form the principal risk driver for all assets. Equities fall into this category, with earnings expectations being the predominant driver of their returns over time. As described previously, labor markets do not have a direct relationship with earnings—there is a sweet spot in which labor market growth is strong enough to support incomes and spending, but not so strong as to erode corporate margins. This sweet spot is where labor markets and earnings expectations move in sync. Outside of this zone, earnings expectations (and, in turn, equities) can move in opposing directions. Crucially, unlike the Treasury market, where the unemployment rate is principally important, it is total employment (which fuels aggregate income and spending) that is the principal driver of the effect of the labor market on equities. Equities require a steady flow of labor to support corporate output, but their earnings depend on whether consumer spending outpaces labor income.

In summation, the labor market is driven by population, participation rates, and unemployment rates. GDP growth is directly driven by employment growth, as it fuels the majority of income and spending. Corporate earnings growth is not directly affected by the labor market but depends on the pace of consumption relative to income, which is supported by employment growth. Fixed-income markets primarily reflect the cyclical tightness or looseness of the labor market, best captured by the unemployment rate. Equity markets depend on the flow of total employment growth to support strong consumption relative to labor income.

Overall, the labor market does not have a homogeneous impact on the economy or markets. Today, we are seeing all of these nuanced linkages manifesting in historic levels of divergence, creating a complex environment for those not following them. We outline how we see these mechanics in motion in the next section.

Mechanics In Motion

We apply the mechanics discussed to today’s context to understand the macroeconomic circumstances. Aggregate employment has begun to falter, but this decline comes from a declining workforce rather than rising unemployment:

Said differently, this weakness isn’t coming from cyclical weakness, but rather from a secular shift in demographics over an unusually short time frame. This weakness in employment, regardless of its source, is a weight on real GDP:

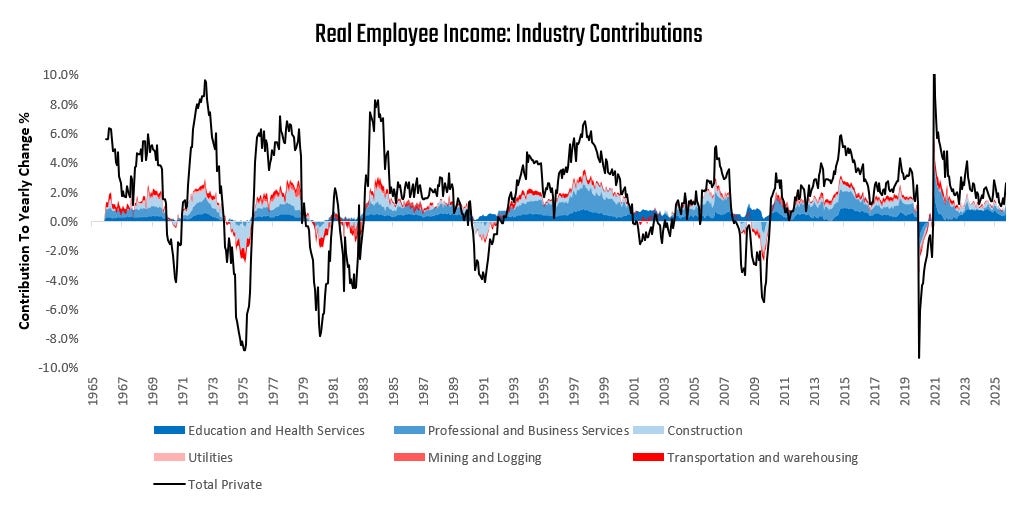

However, despite weakness in labor growth, real wage growth has been strong, supporting strong real incomes:

This rise in real wages has offset the weakness in labor market growth, supporting output. Therefore, even though employment has dragged on GDP growth, output per worker has readily offset this weakness.

While output per worker has powered higher incomes, consumer spending has moved faster than incomes, resulting in a meaningfully positive impulse to corporations’ earnings:

Above, we show our estimate of the impulse to corporate profits from the balance between households’ spending and their income. This dis-saving continues to be a material support to earnings.

Turning to markets, the lack of a rise in unemployment rates continues to limit the need for the Fed to react with monetary easing:

While the profit impulse from households continues to support extremely strong earnings:

Applying our template for how labor conditions impact the economy and markets, we see a labor backdrop that is indeed weak, but weak for non-cyclical reasons. The guideposts for a regime change will be an increase in cyclical unemployment, a decline in real wage rates, and a deceleration in consumption relative to income. Until these shifts, the labor market will likely continue to support equities and weigh on fixed income.

Until next time.